Greek Migration and the Quiet Diaspora (7th–6th Century BC)

Not all great journeys begin with orders from a city-state. In the 7th and 6th centuries BC, the Greek world expanded not just through formal colonization but through something more personal—and often more unpredictable: independent migration.

This was a time when many Greeks took to the sea without a charter or a plan, driven by ambition, necessity, or escape. They were merchants, farmers, craftsmen, and political exiles. Some sought fertile land or safer homes. Others followed trade winds and instinct, carving out new lives far from the coasts of the Aegean.

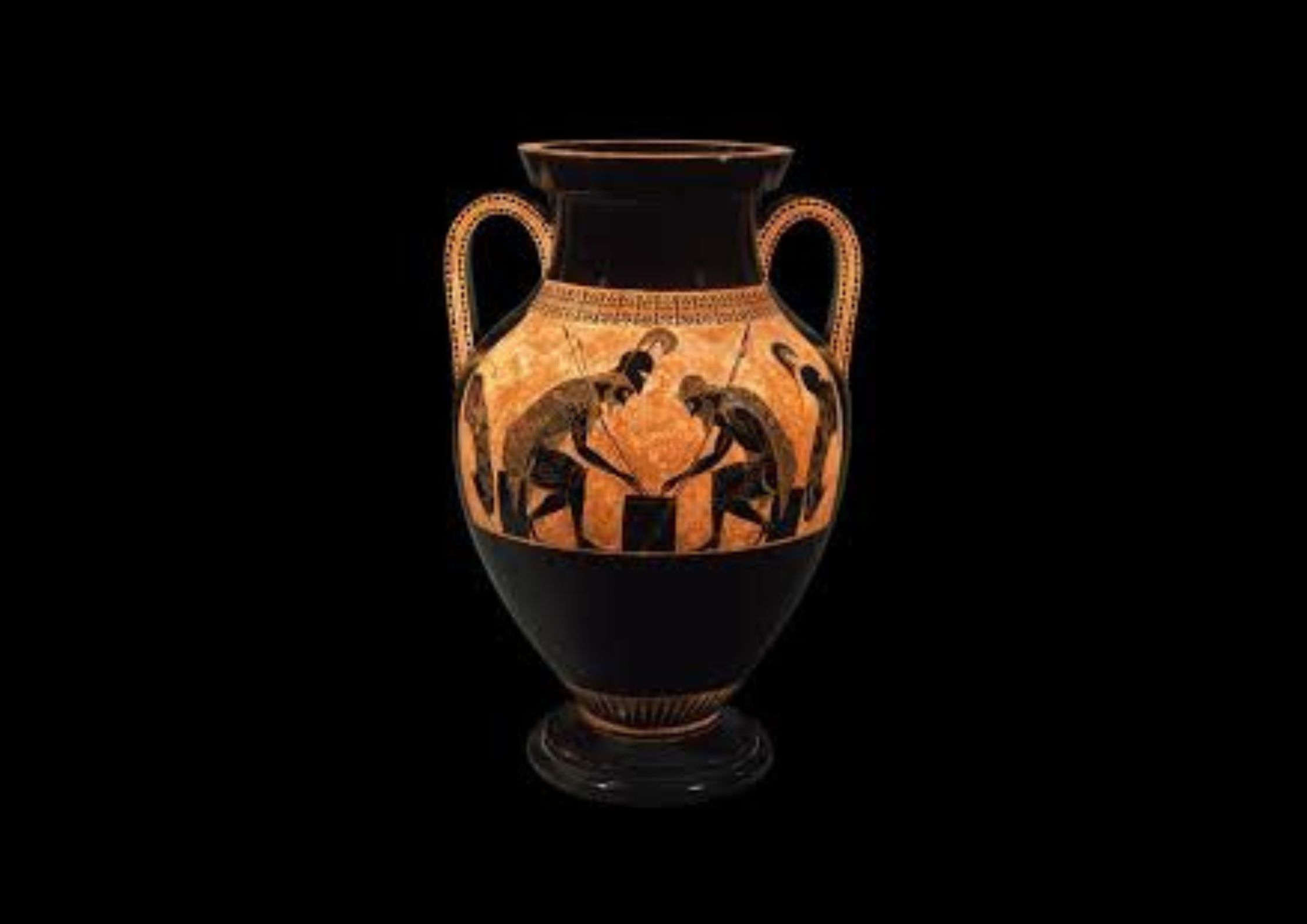

These migrants didn’t always build cities from scratch. Many settled in existing communities, ports buzzing with exchange, towns under foreign kings, borderlands where cultures met and blurred. There, they established small enclaves, trading Greek wine and pottery for local grain and metals, offering craftsmanship in return for protection or acceptance. They brought their gods and customs with them, setting up modest shrines and speaking their native dialects. Yet over time, they adapted too—learning new languages, marrying locals, sharing rituals.

Trade played a central role in this quiet diaspora. The Mediterranean had become a highway of goods and ideas, and Greek merchants were everywhere: in Egyptian markets, Phoenician harbors, and Etruscan festivals. Some intended only to stay for a season. Others stayed for generations. Economic ties deepened into cultural exchange, and what began as a marketplace became a melting pot.

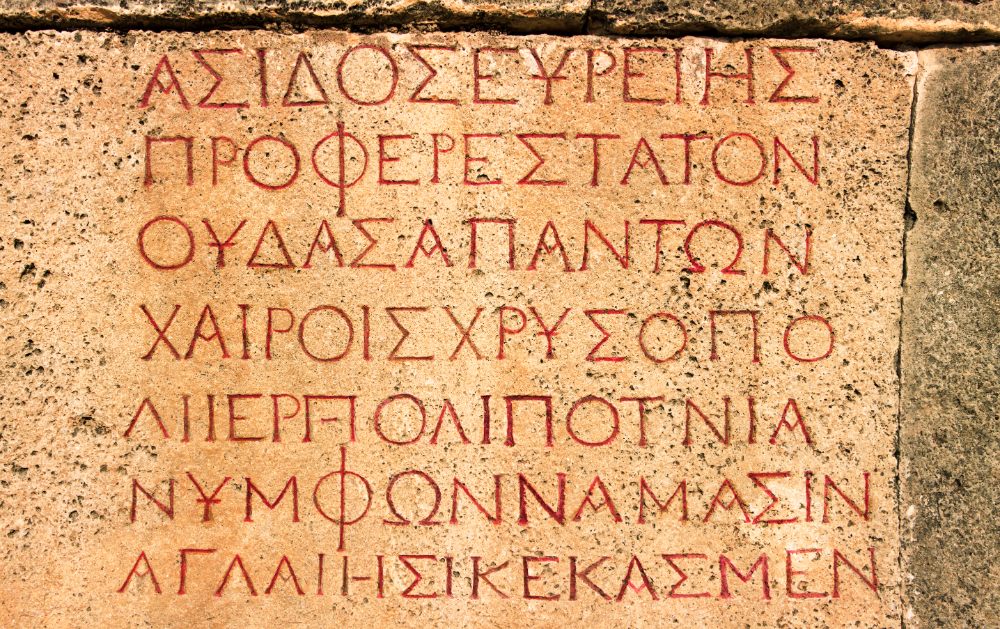

These migrations reshaped the cultural landscape of the Mediterranean. Independent Greeks introduced Hellenic styles in regions where no colony had been founded. They preserved their identity—not through isolation, but through interaction. They lived between worlds, both Greek and something else. Their presence left traces: a Greek word in a local inscription, a terracotta figurine in a foreign grave, a fusion of mythologies carved into stone.

The Greek diaspora of this period reminds us that history is not always made by institutions. Sometimes, it is made by individuals—moving, adapting, surviving. These early wanderers didn’t carry the authority of a polis, but they carried a culture. And in their hands, Greek identity became something fluid, portable, and resilient.

What emerged was not just a story of expansion, but of entanglement. A world where borders were porous, identities were negotiable, and migration was not conquest—but connection.

Image generated by AI using OpenAI’s DALL·E