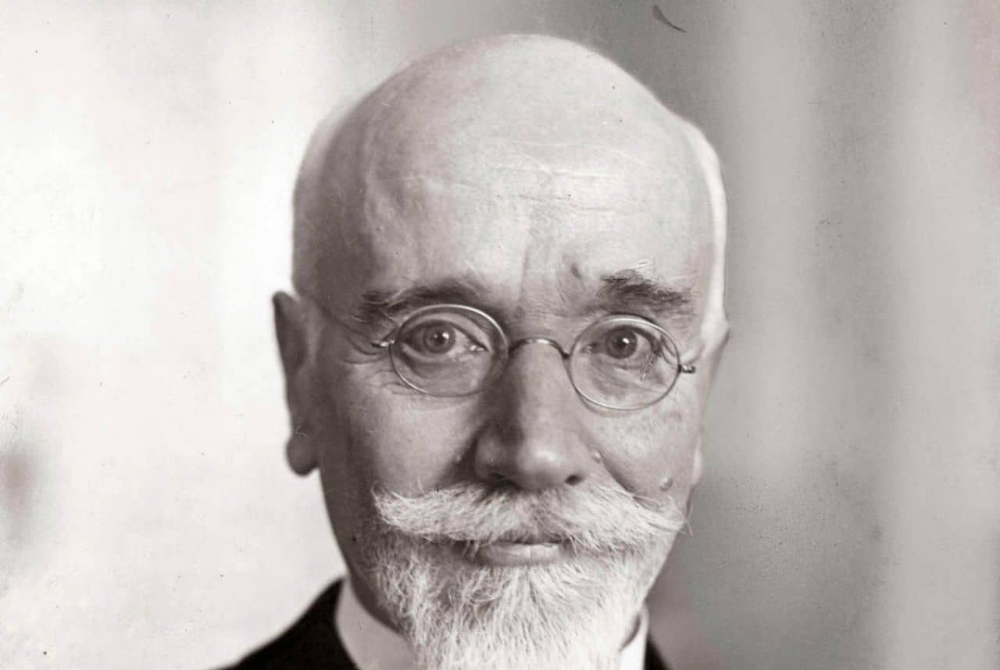

The poet who turned Greek summer into language

He once said, “I owe everything to the light.” And if you’ve ever read even a single line by Odysseas Elytis, you believe him.

There are poets who write about nations. Elytis gave one a soul. Not by proclaiming or declaring, but by whispering — gently, precisely, like the Aegean wind curling through a cypress tree in August. His poems are not just written on paper; they are carved in sunlight, suspended in sea salt.

Born Odysseas Alepoudelis in Crete in 1911 and raised in Athens, Elytis grew up between the intellectual aspirations of a well-off family and the raw beauty of a land that never asked to be explained. From an early age, he knew he wasn’t made for business. He walked away from his family’s soap empire to pursue a life shaped by poetry — and the elements.

His early influences were Greek tradition and French surrealism, but he distilled both into something uniquely his own. He believed Greece could be understood not through history books or ideology, but through olive trees, bare hillsides, and the “a thousand-petaled light” of the Cyclades. To read Elytis is to be there — not as a tourist, but as someone who belongs. And he made you feel that way, even if you had never set foot on Greek soil.

His most celebrated work, To Axion Esti, is often described as a national epic, but Elytis never cared much for epics. What he offered instead was reverence. He sang of the land, of the sacred in the ordinary — of church bells ringing on windblown hills, of saints painted on salt-stained chapels, of the quiet dignity of suffering. He did not romanticize Greece. He simply listened to it. And in doing so, gave it voice.

But it is in Monogramma where Elytis perhaps speaks most directly to the soul. It is a love poem, yes — but also a lament, a hymn, a metaphysical wandering. In it, the beloved becomes an island, a memory, a promise never kept.

“I’ll mourn always—you hear me?—for you, / alone, in Paradise,” he writes.

And later, he imagines a place that might just be a version of Ερημονήσι, the “deserted island” we all carry in us:

“In Paradise I’ve spotted an island / indistinguishable from you / and a house by the sea…”

Elytis understood that even in paradise, there is longing. That summer — real Greek summer — is not just beaches and brightness. It is stillness, ache, the sound of cicadas under the weight of memory. It is solitude dressed in blue and white.

He rarely appeared in public. He refused to be a celebrity, even after winning the Nobel Prize in 1979. He lived a quiet, introspective life — at one time in Kypseli, on Ithakis Street — listening, writing, reflecting. The kind of life where the light itself became his collaborator.

He died in 1996, but no one who has read him believes he is gone. Because somewhere, in a quiet room in the Aegean, sunlight still falls exactly the way he described it. And someone — maybe you — reads a line and realizes: this is what it feels like to be Greek. Or to wish you were.

Elytis never needed to shout. He simply wrote what was true.

And that, always, was enough.