Humor, Censorship, and Victory Against Italy

Censorship in Greece during the 1930s was heavily shaped by the political climate under Prime Minister Metaxas’s regime. Established after a military coup in 1935, Metaxas’s authoritarian rule sought to consolidate power and suppress dissent, closely aligning with fascist Italy in ideology and control tactics. The regime imposed strict censorship laws on the press and radio, restricting the content that could be publicly circulated. Consequently, cartoonists and media outlets had to exercise caution, avoiding any criticism or ridicule of foreign powers, especially Italy, as Greece maintained a policy of neutrality at the outset of World War II.

Interestingly, Greece’s tradition of satirical humor has ancient roots, dating back to the 5th century B.C. when Aristophanes used comedy and satire to critique Athenian society and politics. This rich history of humor as a form of social and political commentary persisted through the centuries, and by the 20th century, Greek cartoonists began to leverage satire as a weapon of resistance. During the early years of World War II, Greece’s neutral stance meant that negative comments about belligerents were forbidden, and only light-hearted, non-political cartoons about everyday life were permitted. However, this changed dramatically when Italy invaded Greece on October 28, 1940.

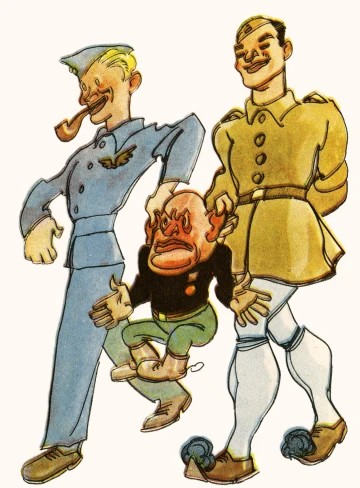

Initially, Greek media responded with restraint, adhering to censorship laws. But once Italy declared war, Greek cartoonists and media organizations were unleashed, producing sharp, humorous cartoons that mocked and derided the Italian invaders. These cartoons became a powerful form of resistance, bolstering national morale and showcasing Greek resilience. Despite the Italian defeat at the Battle of Greece in 1941—where Greek troops remarkably repelled Italian forces—humor persisted. Greek cartoonists continued to depict their enemies with satire, emphasizing the fiasco of the Italian campaign. Using humor as a weapon stood in stark contrast to the absence of Italian and German cartoons during this period. Mussolini detested cartoons, dismissing them as “Anglo-Saxon decadent art,” and the Germans, as documented in Goebbels’ diary, forbade ridiculing the Greeks, fearing it could undermine their occupation efforts.

In sum, Greek cartoons during the Greco-Italian War exemplify how satire served as a potent tool of psychological resistance and national pride. From ancient comedic traditions to wartime propaganda, Greek humor persisted as a subtle yet powerful form of defiance amidst the constraints of censorship and war.