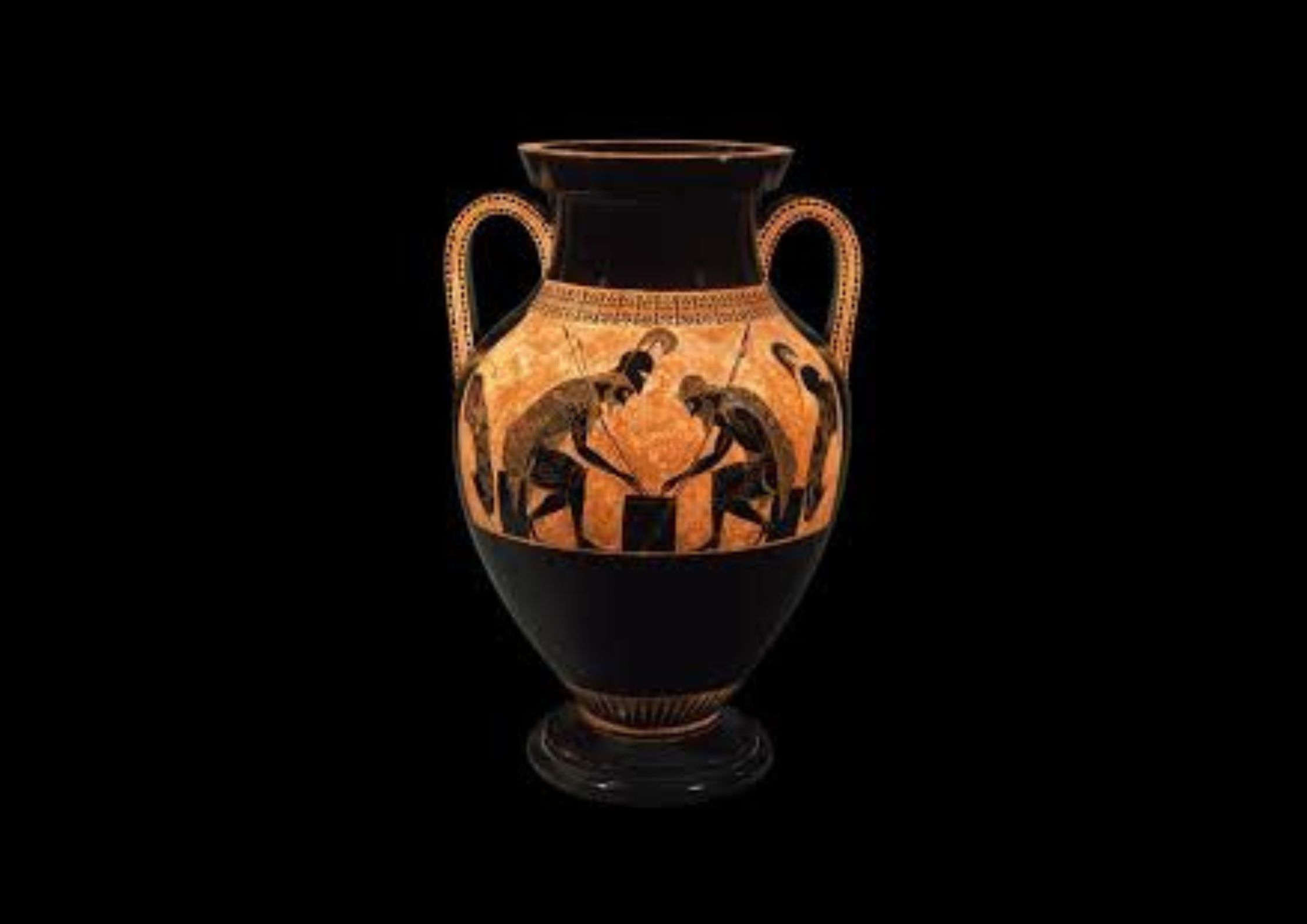

How Anatolia Shaped the Soul of Greek Pottery (8th–6th Century BC

Some of the most important shifts in ancient Greek art didn’t begin in Athens or Corinth—but across the water, along the rugged coastlines of Anatolia. Here, in the borderlands between Greece and Asia, pottery became a language of innovation. During the 8th to 6th centuries BC, this region—modern-day western Turkey—served as a creative frontier where Greek artisans absorbed Eastern techniques, symbols, and ideas, and transformed them into something distinctly their own.

This so-called Anatolian period of Greek pottery coincided with the flowering of Greek colonies in Ionia, Aeolis, and Caria. These were places of exchange, not isolation. Greek potters, living alongside Phrygians, Lydians, and Near Eastern merchants, encountered new motifs: lions, sphinxes, floral rosettes, and composite creatures. They responded not by copying, but by fusing. The result was a bold new style—part Geometric logic, part Eastern flourish.

This is where we begin to see the shift from strict patterns to living figures. The early Orientalizing style still clung to symmetry and borders, but suddenly the vases told stories: of gods, heroes, and ordinary life. Mythology spilled across curved surfaces. Horses galloped beneath the handles. Grievers bent over funerary scenes with raised arms, echoing real rituals.

Technically, too, these potters were innovating. Anatolia offered rich clay, and firing techniques evolved. Black-figure pottery—born in Corinth and spread east—allowed artists to carve figures into black slip, creating rich silhouettes. Later, red-figure painting reversed the process, letting brush and line define muscle, motion, and expression. The detail became more human. The gods looked like neighbors.

These pots were not just decorative. They moved: through trade, gift-giving, and ritual. They served wine at symposia, honored the dead, and decorated sanctuaries. Their very existence is evidence of interaction—between peoples, aesthetics, and worldviews.

What the so-called Anatolian pottery period really shows us is that Greek art was never isolated. It was born in motion—on ships, at marketplaces, in conversations between cultures. The legacy of these pots is not only in their beauty, but in what they reveal: that Greek identity was forged, in part, by looking outward.

Photo: ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons.