Hellenistic Identity Through the Fusion of Greek and Eastern Traditions

The Hellenistic period (323–146 BC) was marked by more than territorial expansion—it was a cultural revolution. As Alexander the Great’s empire fragmented, his successors ruled over a diverse array of peoples from Egypt to Persia. Greek culture, language, and ideas spread across these regions, but they did not erase local traditions. Instead, what emerged was a dynamic synthesis—a blend of Greek and indigenous customs that reshaped identity, art, religion, and society.

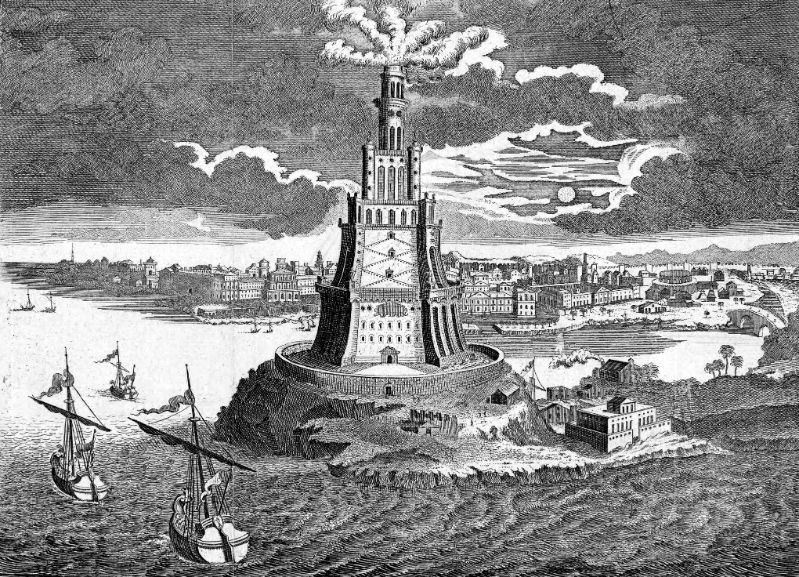

This fusion is especially visible in urban development. Cities like Alexandria in Egypt, Seleucia on the Tigris, and Antioch in Syria became centers of Greek language and architecture while also accommodating local deities and traditions. Greek-style theaters and gymnasia stood alongside temples to Eastern gods, reflecting a negotiated coexistence of cultures.

In religion, syncretism was common. Greek gods were equated with local deities—Zeus-Ammon in Egypt and Serapis, a Greco-Egyptian deity, are striking examples. This wasn’t mere imperial propaganda; these hybrids reflected genuine religious evolution and the spiritual needs of increasingly multicultural populations.

Art and sculpture from the Hellenistic period also display this fusion. Traditional Greek realism remained, but emotional expression and dramatic movement intensified, possibly influenced by Eastern artistic styles. In regions like Bactria and Gandhara (modern Afghanistan and Pakistan), Greek forms merged with Buddhist iconography, producing the first anthropomorphic images of the Buddha—a powerful example of trans-cultural artistic dialogue.This era of cultural entanglement challenges the idea of Hellenization as a one-way process. While Greek elements did dominate elite and administrative spheres, they were constantly shaped by local traditions. The result was not a single Hellenistic culture, but many hybrid identities that bridged East and West.