The Stylized Bridge Between Geometric Rigidity and Archaic Naturalism

Daedalic art marks a fascinating transitional phase in the development of ancient Greek visual culture, bridging the abstract stylization of the Geometric period (c. 900–700 BC) and the more naturalistic tendencies of the Archaic period (c. 600–480 BC). Named after the mythical craftsman Daedalus—credited with creating lifelike statues in myth—this style flourished mainly between 700 and 500 BC. It reflects a period of experimentation, where Greek artists began to reshape their visual language while remaining rooted in past conventions.

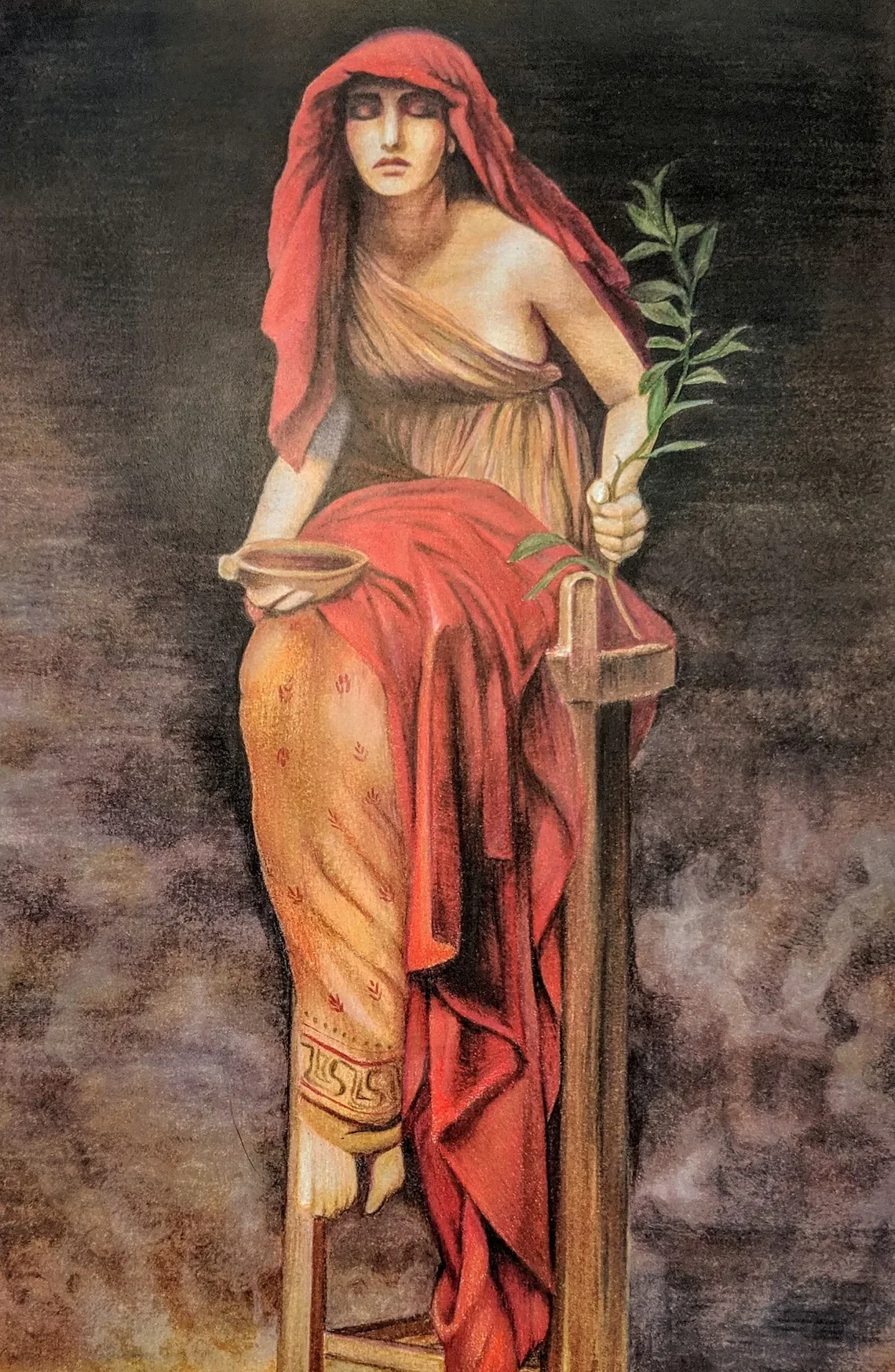

In sculpture, Daedalic art is characterized by a schematic approach to the human form. Figures stand rigid and frontal, with arms close to the body, reflecting a lingering geometric influence. Yet within this rigidity lies an effort to push boundaries. Proportions become more consistent, hinting at an interest in realism. Facial features—especially large almond-shaped eyes and simplified mouths—are iconic rather than naturalistic, giving the figures a symbolic presence rather than an individual identity. One of the most distinctive features is the treatment of hair: thick, patterned locks frame the face in a stylized and decorative manner, often cascading in geometric rows or braids. These elements combined give Daedalic sculpture a unique identity—anchored in tradition but straining toward lifelike form.

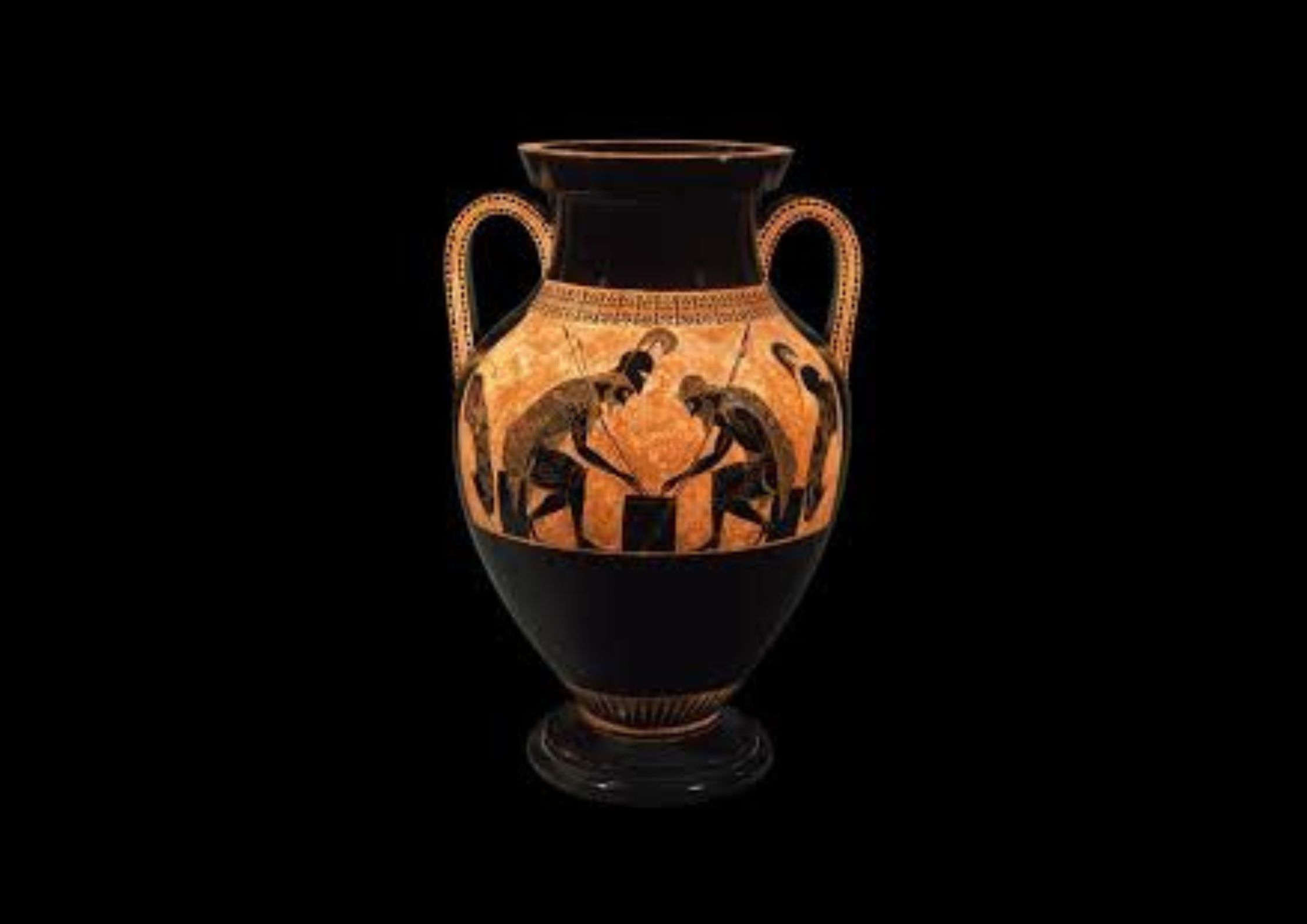

Pottery from the Daedalic phase reflects similar tendencies. Designs remain highly geometric, and the color palette is limited—usually dominated by black and red slips. However, human and mythological figures begin to appear alongside traditional motifs. These early visual narratives mirror the sculptural style in their schematic renderings, offering a unified aesthetic across media.

Among the best-known examples of Daedalic art is the Lady of Auxerre, a limestone statuette whose rigid stance and detailed hair perfectly encapsulate the style’s defining features. The Nikandre Kore from Naxos, carved in marble and intended as a votive offering, also demonstrates the Daedalic blend of stiffness and stylization, with early attempts at realistic garment drapery. Even works like the Charioteer of Delphi, though more advanced, retain traces of the Daedalic foundation, showing how the style continued to influence Greek art as it evolved.

The cultural context of Daedalic art reflects broader influences from Egyptian and Near Eastern traditions, especially in the formalized posture and facial presentation. At the same time, many of these figures held religious significance, often dedicated in sanctuaries as offerings to the gods. This blend of symbolic form, external influence, and devotional function speaks to the richness of the era.

Ultimately, Daedalic art represents a critical moment of stylistic transformation. It laid the groundwork for the Archaic style’s embrace of motion, emotion, and naturalism, serving as both a legacy of past ideals and a catalyst for new artistic directions.