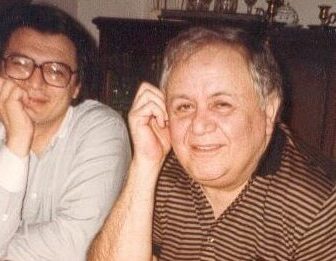

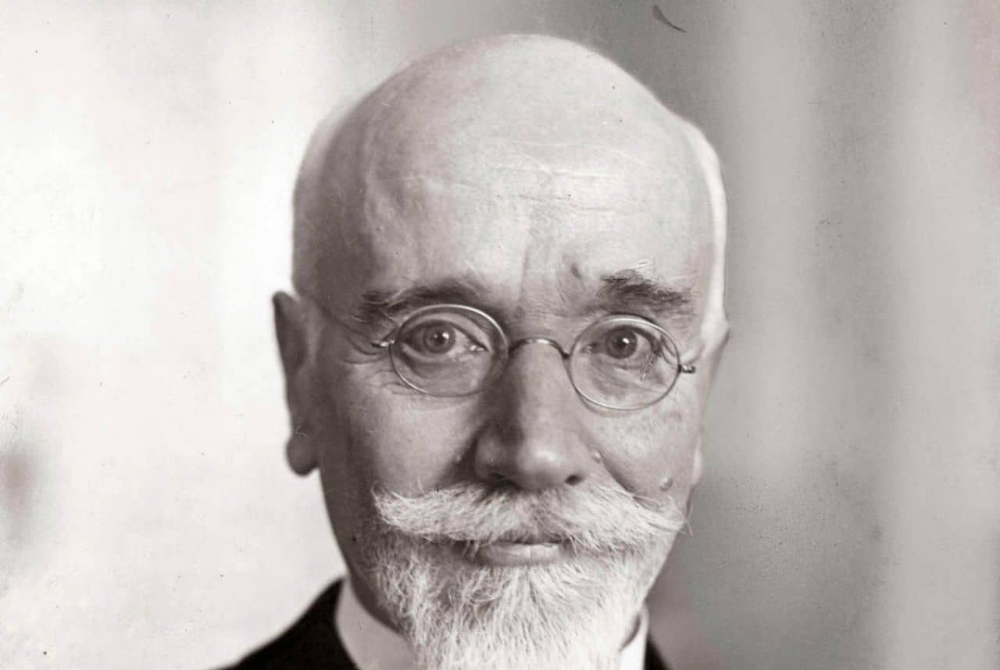

It was 1961. From the moment I met the great composer, we shared a strong understanding and trust.

By Dimitris Vernikos

My acquaintance with Manos Hadjidakis in October 1961 was marked by an immediate and spontaneous mutual understanding. Obviously, not for exactly the same reasons, but for similar emotions. For me, he was a great light in the tunnel of my personal life at the time — a sun. For him, I was a young person for whom he sensed he could give without feeling that “he was not getting back even a millimeter of what he gave,” as he characteristically writes in one of his letters from the vast correspondence of 1967–1972. “He was reading,” he writes, “old diaries from ’56–’57 and wondered about his immense expenditure of self.”

Manos had the habit — or rather the need — from a very young age, of writing a daily diary about what he was thinking and what was happening to his life. I mention this because I believe that this extensive and frequent correspondence brought him back to that familiar practice — only this time, his writings were addressed to me, and moreover, I think, with the conscious wish that part of these letters might one day be published.

From the time of our acquaintance until 1967, there are 14 letters, written during periods when we were apart — in America or Europe. The overwhelming correspondence of 1,300 pages begins in 1967 and continues until 1972, when Manos was in America. The sheer volume of this correspondence explains, on one hand, the need for a specific and structured communication — for Manos was an abundantly communicative person — and on the other hand, his desire to channel his thoughts on a complete and all-encompassing level. He was 42 years old, full of experience and creativity.

The occasion for what was initially meant to be a short trip to America came from a new episode with what he himself considered the traumatic Never on Sunday, this time for its adaptation into a Broadway musical titled Ilya Darling.

The year 1966 was already filled with productions. At the beginning of the year, the album Mythology was released; in May, he composed the music for the theatrical adaptation of Captain Michalis by N. Kazantzakis, directed by Manos Katrakis, which later became an album.

In the summer, preparations and rehearsals for Ilya Darling began in Spetses with Jules Dassin, Melina Mercouri, and Joe Darion, the lyricist. They discussed the subject, wrote lyrics, and composed some songs. Later, in Athens, some songs were recorded in the studio — for example, In Lavrio There’s a Dance Tonight, Who Will Be the Lucky One — which Manos himself sang (or rather, interpreted) to show Melina how it should be performed. The foundations and planning for Ilya Darling were now in place. After all this work, Dassin and Darion departed.

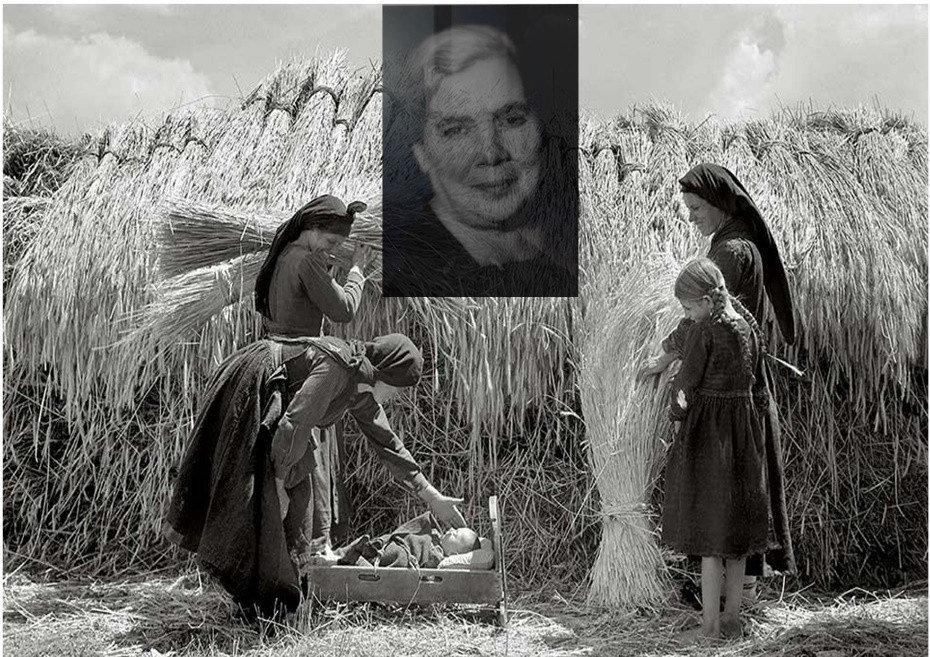

In September, the actors Vasilis Diamantopoulos and Maria Alkaiou, who were in financial difficulty, pressed Manos to write music for Koromilas’s play The Fortune of Maroula. They agreed to cover the studio and musicians’ fees, and Manos would retain all rights to the songs and music. Manos entered the studio for 2–3 days, composed, orchestrated, and recorded about 30 instrumental themes and songs.

Dimitris Vernikos

AUTHOR’S NOTES

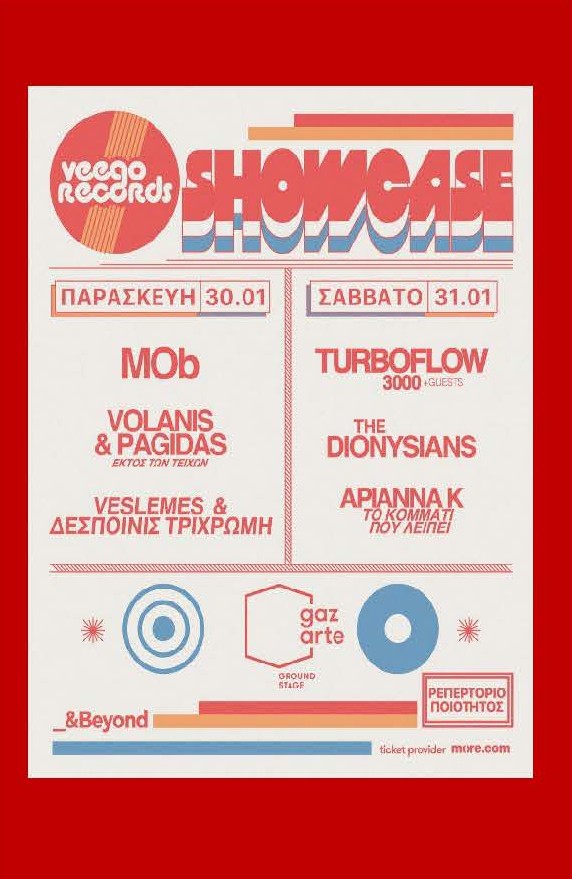

The above piece was used for the Introduction of the presentation of my correspondence with Manos Hadjidakis at the Sorbonne University in Paris on the 22nd of November 2025. Much of this material was later used in Ilya Darling and subsequently in the albums Episrofi (Return) and The Gold of the Earth.

At the end of that October, Manos went to America, and in December his mother and I followed. In early 1967, trial performances of the show began — in Washington, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Toronto. The premiere took place on April 12 at the Mark Hellinger Theater. On April 21, the military junta came to power in Greece. As he reveals in one of his letters from that time, Ilya Darling, combined with the junta and Melina’s explosive temperament, led to the most intense conflict in their relationship, which temporarily broke off.

With the coming of the junta, Manos officially entered his “American period,” which lasted until the end of 1972. The correspondence had already begun in February 1967 and gradually, after the premiere, became more frequent — almost daily.

In one of his long letters, which begins on New Year’s Day 1971 — on the fifth page (by then January 2) — he writes:

“Yesterday, I didn’t feel that the letter I wrote you was finished. So it turned into a letter-diary, or a novel, if you prefer…”

This practice was very common throughout that stormy period of correspondence, particularly on Manos’s part.

In the presentation to Sorbone, I attempted to weave together excerpts from Manos’s letters, enriched with photographs of the time and some of my own commentary, in order to convey something of the atmosphere — and of Manos himself — during his American years.