Crete’s distillation festivals

Across the hinterlands of Crete, when the grape harvest concludes and autumn begins, the landscape is overtaken by a distinctive, pungent fog. This marks the beginning of Rakokazana, a centuries-old institution that serves as both a distillation process and a frantic social festival. Inside stone huts and repurposed barns perched on mountainsides, the air becomes heavy with the humidity of boiling steam and the sharp tang of crushed grapes, signaling the production of tsikoudia, the island’s ubiquitous clear spirit.

The focal point of the event is the kazani, a massive copper still that acts as the hearth of the community during these weeks. Into its belly goes the strafyla—the fermented mash of seeds, skins, and stems left over from winemaking. Through a crude but effective alchemy involving intense heat and water cooling, this agricultural byproduct is transformed. However, the Rakokazana is rarely a solitary industrial task; by custom, it is an exercise in radical hospitality.

Because the distillation takes hours, the waiting period evolves into a spontaneous feast. Tables are crowded with locals, while potatoes are buried in the hot ashes of the distiller’s fire to roast alongside grilling meats. The soundscape is frequently dominated by the frenetic bowing of the Cretan lyra and the recitation of mantinades, improvised rhyming couplets shouted over the din of conversation.

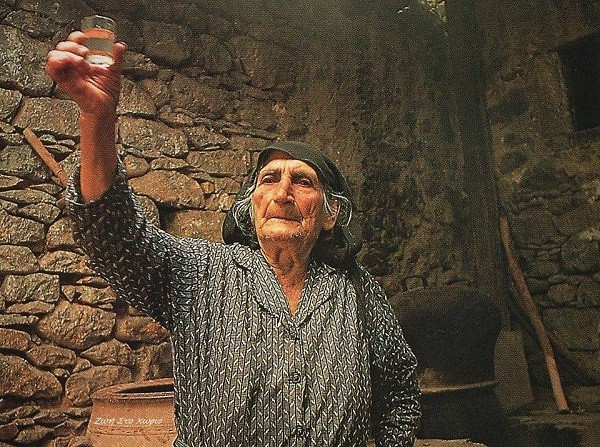

The ritual culminates in the collection of the protoraki, the very first flow of the distillate. Extremely potent and often testing the limits of palatability, this initial run is celebrated as the essence of the harvest. Ultimately, the Rakokazana distills more than just alcohol; it preserves the social fabric of the village, bottling the heat of the summer sun to serve as warmth against the coming winter.