A Living Monument of Early Byzantium

Nestled at the foot of Mount Sinai — one of the most sacred sites in Christian, Jewish, and Islamic tradition — the Monastery of Saint Catherine (Agia Aikaterina) is among the oldest continuously inhabited Christian monasteries in the world. It was founded in the mid-6th century CE by order of Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565), placing it firmly within the Greco-Byzantine era. The emperor commissioned the fortified complex to protect a community of monks and pilgrims near the site traditionally identified as the location of Moses’ encounter with the Burning Bush.

The monastery exemplifies early Byzantine imperial architecture, with its thick granite walls, basilica plan, and materials transported from different parts of the empire. Its main church — the Basilica of the Transfiguration — houses some of the earliest and finest surviving Christian mosaics, especially the famous 6th-century apse mosaic of the Transfiguration, which reflects a stylistic transition from classical Roman art to Christian iconography.

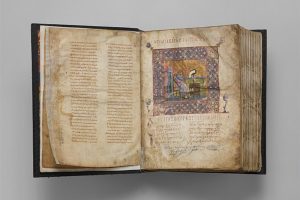

Beyond its religious function, the monastery became a vital center of Greek Orthodox spirituality and scholarship. Its library is the second largest collection of early Christian manuscripts in the world, after the Vatican Library. It preserves Greek biblical texts, works of the Church Fathers, and numerous classical Greek writings, as well as Syriac, Arabic, Georgian, and Coptic manuscripts, reflecting the multilingual and cosmopolitan nature of the Byzantine frontier.

Remarkably, the monastery survived the Islamic conquests of the 7th century and beyond — in part thanks to a document of protection (achtiname) attributed to the Prophet Muhammad. While the historical authenticity of the original document is debated, its symbolic value and repeated confirmations by later Muslim rulers helped ensure the monastery’s continued operation and relative autonomy.

Today, Saint Catherine’s is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Regardless of this protection, a recent ruling by Egypt’s Ismailia Administrative Appeal Court, declared that Egypt owns the land on which the Greek Orthodox monastery sits while upholding the monks’ right to worship and use the site.

Though Egyptian officials have repeatedly reassured Greek counterparts that the court’s decision will not impact the monastery’s religious standing or autonomy, the ruling has raised alarm in Athens and among the Greek Orthodox Church hierarchy, prompting diplomatic engagement at the highest level.