The Foundations of Western Higher Education

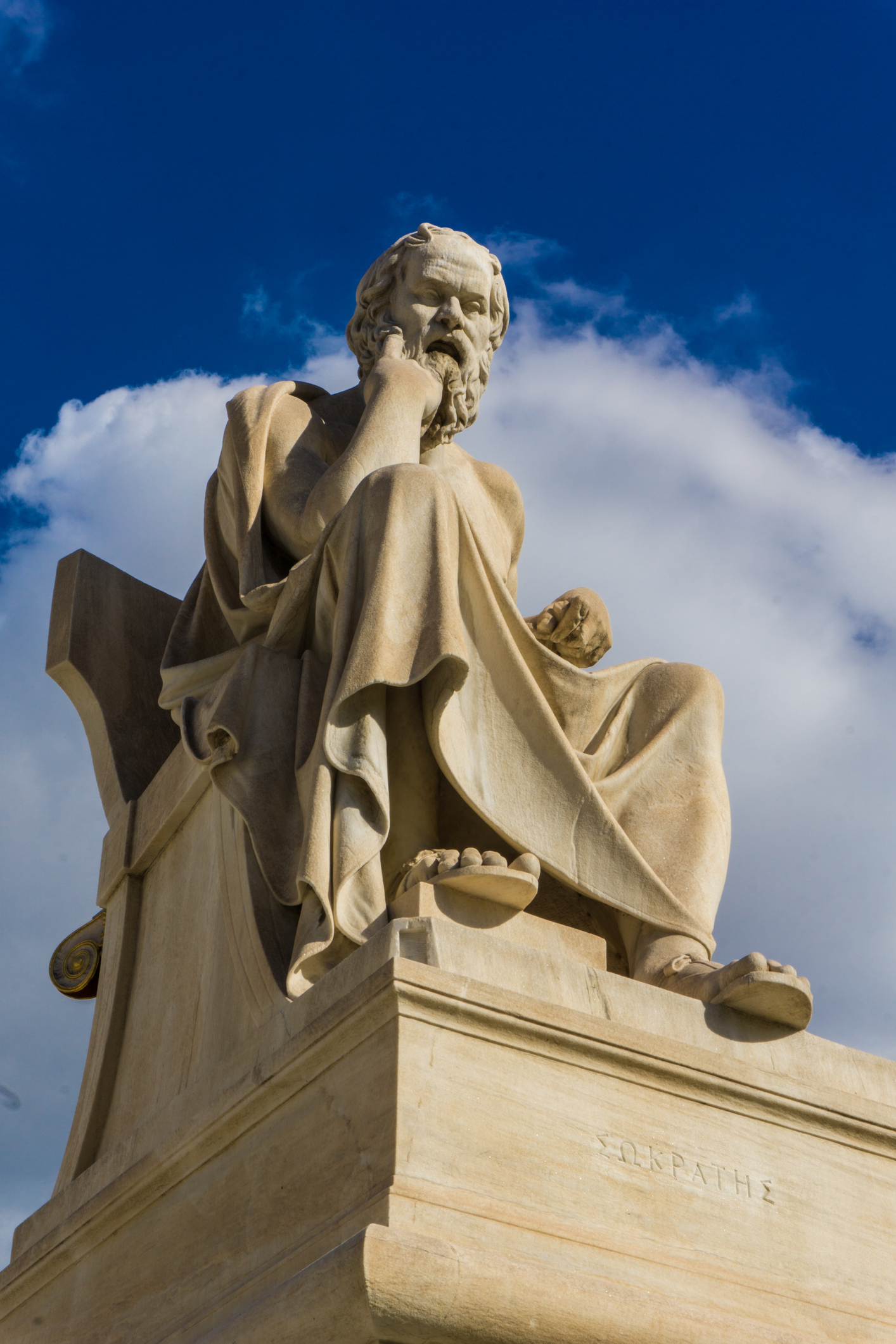

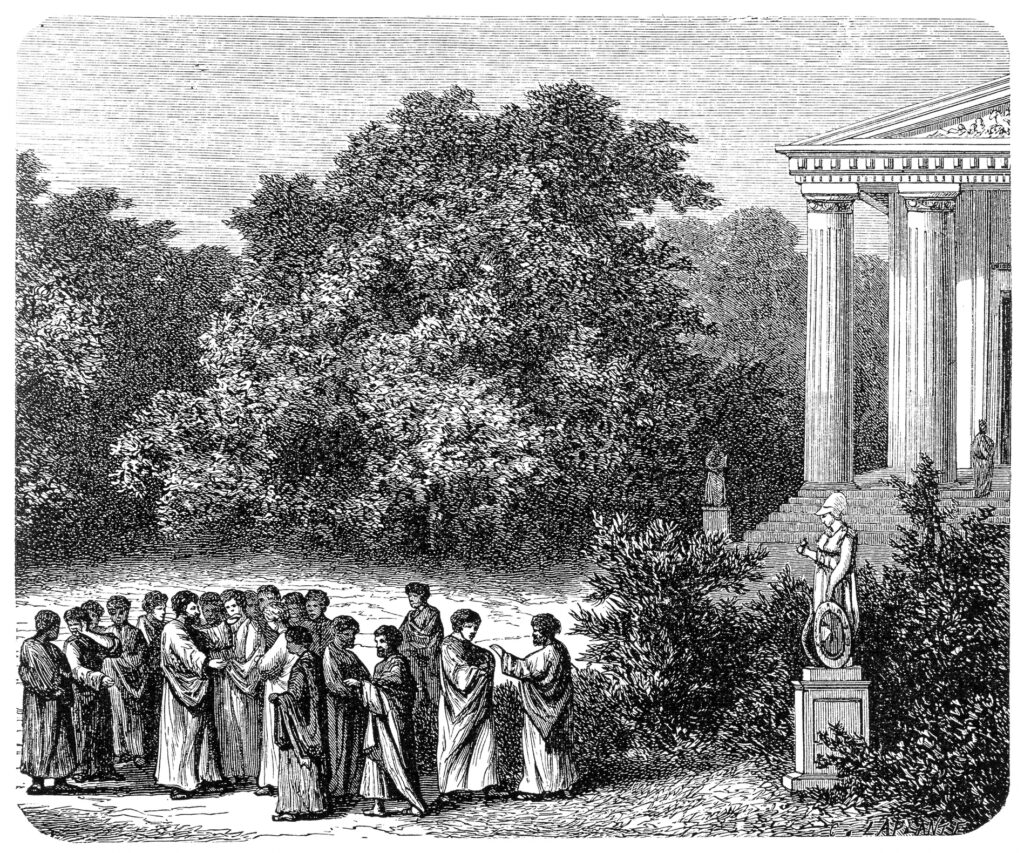

In approximately 387 BC, the philosopher Plato established the Academy in Athens, widely considered the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Located in a grove sacred to the hero Academus, the Academy served as a center for philosophical inquiry, scientific research, and intellectual discourse for nearly nine centuries.

Plato’s vision for the Academy extended beyond mere instruction. It aimed to cultivate individuals capable of discerning truth and governing justly, reflecting his belief that philosophical understanding was essential for good leadership. The curriculum was broad, encompassing philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and dialectic, with an emphasis on critical reasoning and intellectual rigor.

Among its notable students was Aristotle, who spent two decades at the Academy before founding his own school, the Lyceum. The Academy attracted scholars and thinkers from across the Greek world, fostering a vibrant intellectual community. Its enduring legacy lies in its pioneering role as a research and teaching institution, establishing a model for academic pursuits and intellectual communities that profoundly influenced the development of Western thought and education.