Discovering Ancient Wealth

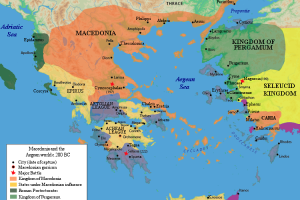

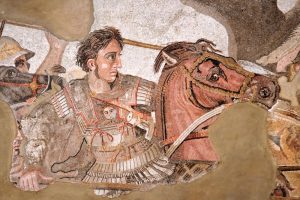

The archaeological site of Vergina, located in northern Greece, reveals the rich history of the ancient Macedonian kingdom, particularly under the rule of Philip II and his son, Alexander the Great. Among its most significant discoveries are the royal tombs, unearthed in 1977 by archaeologist Manolis Andronikos. These tombs provide invaluable insights into the grandeur of Macedonian burial customs and the wealth of its rulers.

One of the most striking tombs, believed to be that of Philip II, is adorned with exquisite frescoes depicting scenes of hunting and battle, symbolizing the king’s martial prowess and divine favor. The entrance to the tomb is marked by an impressive façade, highlighting the importance of the occupant. Inside, the treasures are staggering: golden wreaths, intricately crafted weapons, and ceremonial items reflect the opulence of the Macedonian elite.

The stories embedded within these tombs speak of a bygone era when Macedon was a dominant power in the ancient world. The discovery of the contents, including a magnificent golden larnax—a burial box containing the remains of the deceased—shone a light on the funerary rituals that honored their complexities and aspirations.

Today, Vergina stands as a testament to the art, politics, and culture of ancient Macedon. As visitors wander through the site, they are transported back in time, bearing witness to the legacy of those who once ruled an empire, forever etched in the stones of these royal tombs.