A Tribute to the Poet on Ios

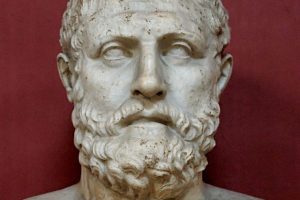

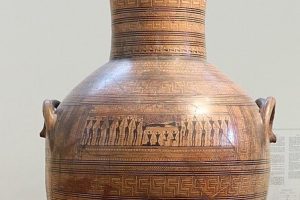

Homer’s grave on the Greek island of Ios is traditionally believed to be the resting place of the legendary ancient Greek poet credited with composing the “Iliad” and “Odyssey.” Although the exact location and even the historical existence of Homer remain subjects of debate among scholars, the site has become an important cultural landmark. Some theories suggest Homer may have been blind and lived around the 8th century BC, while others propose different timelines. Ios, a Greek island in the Cyclades, was known in antiquity for its contributions to arts and culture. The island’s strategic location in the Aegean Sea made it a hub for trade and travel, likely providing Homer with the inspiration for his epic tales of heroism and gods.

The village of Chora on Ios, with its whitewashed buildings and narrow streets, continues to thrive as a lively center that contrasts with the solemnity of the grave site. Historically, Ios was also famous for its role in the Greek War of Independence in the 19th century, contributing to Greece’s modern national identity. Today, visitors to Homer’s supposed burial site often reflect on the significance of oral tradition and storytelling in Greek culture, connecting ancient history to the present day.