The First Woman Olympic Victor

Cynisca of Sparta was a Spartan princess and the first woman recorded to have won an Olympic victory in ancient Greece. She lived in the 4th century BCE, during the height of Sparta’s influence, and belonged to the Eurypontid royal line as the daughter of King Archidamus II and sister of King Agesilaus II.

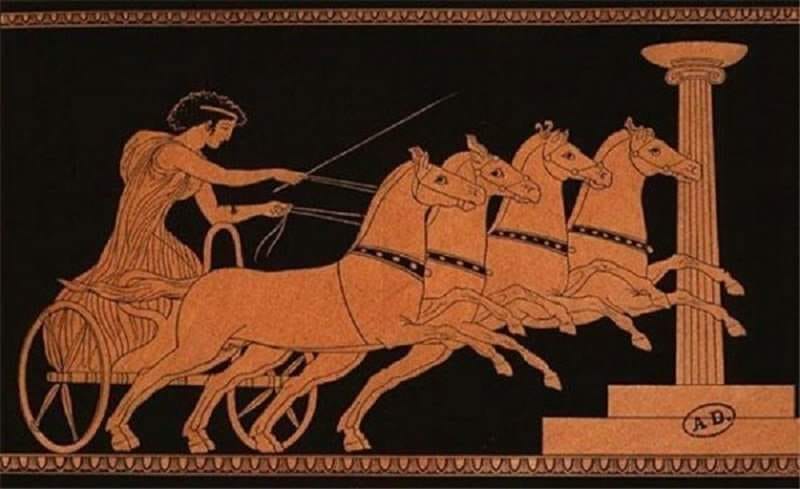

In ancient Greece, women were generally excluded from participation in the Olympic Games, both as athletes and as spectators. However, the four-horse chariot race (tethrippon) recognized the owner of the horses and chariot as the victor, not necessarily the driver. This rule created a narrow path for women of great wealth and status to claim Olympic titles, at least in theory. Cynisca was the first to do so in practice.

Using her royal resources, Cynisca bred and trained a team of horses that competed at Olympia. She won the four-horse chariot race in the 96th Olympiad (396 BCE) and again in the 97th Olympiad (392 BCE. These victories made her the earliest known female Olympic victor and a notable figure in both Spartan and pan-Hellenic history.

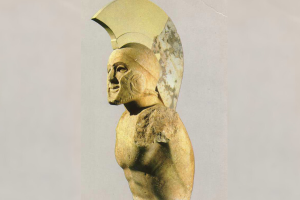

Ancient sources, including Pausanias, report that a bronze statue group of Cynisca and her chariot was erected at Olympia, an extraordinary honor in a sanctuary otherwise dominated by male athletes. The statue bore an inscription that Cynisca herself is said to have composed, declaring with pointed pride that she was “the only woman in all Hellas” to have won this crown. In a culture where women were barred from even watching most Olympic events, her public commemoration inside Zeus’s sacred precinct was quietly revolutionary.

Cynisca’s success was not accidental. Spartan women, unlike their counterparts elsewhere in Greece, could own and inherit property, manage estates, and command substantial wealth. This legal and economic independence gave her the means to maintain elite horse-breeding operations, something far beyond the reach of most Greek men, let alone women. While her brother Agesilaus reportedly encouraged her to compete—perhaps to demonstrate that chariot victories were displays of wealth rather than personal athletic virtue—Cynisca turned that opening into a lasting breach in Olympic custom.

Her victories had ripple effects. After Cynisca, other women, including Euryleonis of Sparta and later Hellenistic queens, entered chariot teams and claimed Olympic titles. What began as a technical loophole became a precedent: women could not run in the stadium, but they could inscribe their names into Olympic history through ownership, strategy, and resources.

Cynisca’s legacy, then, is not merely that she won. It is that she revealed how power operates in rigid systems—how law, money, and intelligence can be leveraged to rewrite what seems immovable. In a world that denied women the body, she claimed the victory through the stable and the ledger, proving that even in ancient Greece, barriers were never quite as solid as they appeared.